Saturday, November 14, 2020

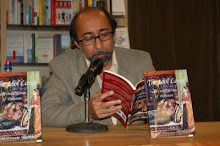

My review of Mudassar Bashir's Punjabi Novella Rekh

Prolific Mudassar Bashir’s latest novella, Rekh, revolves around a character named Ashi, short for Ayesha, who’s on her way to becoming a medical doctor and is in love with her maternal cousin Khalid. In general, the cousins in her family are close to one another and a lot of relatives congregate during wedding ceremonies in the family.

The patriarch Hashim Ali enjoys the love and respect of his four sons and a daughter, who’s the mother of Ashi. Ashi resists her beloved Khalid’s suggestion that they let their parents know about their mutual attraction for each other because she wants to finish her MBBS without distraction. Circumstances, then, force Khalid to marry Ashi’s sister. As more tragedies pile up, Ashi appears to be the worst loser.

Although the title Rekh may suggest that the author intends to explore the concept of predestination and how it shapes our view of our lives, it is also a character study of a strong-willed person. While Bashir studies the character by situating the narrative within an educated, modern, middle-class milieu, he also does so by invoking the price traditional values exact from a person.

Bashir tests the limits of love and sacrifice in a deceptively simple story. Ashi has a chance to marry Khalid again when her sister dies in childbirth but cannot bring herself to share the bed with Khalid after her sister. Ashi chooses instead . . .

You can read the rest here.

Monday, November 9, 2020

The Day the Cookie Froze

Saturday, September 12, 2020

I review Anne Tyler's novel Redhead by the Side of the Road

This is the story of a man in his early 40s whose existence flits between feeling lonely and alone. The two states are not diametrically in opposition to each other, but they are not the same either. The difference is important and central to the story of Redhead by the Side of the Road.

The latest disruption, the one we witness in the narrative, is caused by a young boy, Brink, a runaway, who shows up outside Micah’s patch one morning out of the blue, claiming to be his son because he learned that Micah was the love of his mother’s life when she was young. Quick math puts that speculation to rest, but Micah ends up acquiescing to let him use the guest room just when Cass, his woman friend, is dealing with the fear of being evicted. Cass sees that as a signal from Micha that she is not welcome to move in with him, and no pleading, no amount of explanation would help change her mind. The case is closed. That’s the thick of it.

Micah, in his moments of solitude, looks back, wondering why women would leave him on one pretext or another. There are differences between Cass and him, but they are minor. There’s more care for the suffering in Cass’s worldview than that of Micah’s and he knows it, but their relationship has worked so far because both, as adults, recognize and respect each other’s physical and emotional space. But is there any place in Micah’s world for flexibility, for bending of the rules?

Anne Tyler, one of the most loved American authors of more than 20 novels, does not let the narrative either spin out of control or descend to irreversible tragedy. For the most part, it simmers on a constant low flame. The runaway boy is reunited with his mother and adoptive father, who develops respect for Micah. Cass takes Micah back. Brink’s mother and Micah’s college sweetheart, Lorna Bartell, is allowed to share her perspective with Micah of how and why their relationship fell apart.

This idea of a clash of perceptions between how men and women see certain events unfolding around their lives seems like a common theme now and brings to mind Clifford Garstang’s The Shaman of Turtle Valley, whose protagonist, Aiken, has a similar problem vis a vis the two most important women in his life with a far more serious issue on hand.

Read the rest here.

Sunday, August 16, 2020

Moazzam Reviews Clifford Garstang's The Shaman of Turtle Valley for Heavy Feather Review

"What to Aiken’s mind has always been a matter of betrayal from Kelly when she left town and eventually married after Aiken joined the army, Kelly’s perspective shatters his sense of self. Their last love-making moment, she considers rape."

There’s been a lot of talk, at least since Trump’s victory, about the poor Whites left to rust and rot due to our neoliberal economic policies pursued by the two political parties. We often get stuck with an image of illiterate redneck pockets unable to cope with the evolving nature of modernity and corporate greed. There’s a risk of dehumanizing which must be avoided despite political differences. Clifford Garstang has done a decent enough job to explore the good, the bad, and in-between by focusing his lens on a family whose presence in a small idle place called Turtle Valley, Virginia, goes back generations. For now, Garstang goes after the current generation with Aiken at the heart of the story.

According to one view, America keeps a certain part of its population illiterate and poor, Whites and non-Whites, on purpose to be used as cannon fodder for its imperial wars around the globe. Without any regard for their well-being afterwards if they’re lucky enough to return in one piece. It is not rocket science to see the connection between the Korean War and onward to a rising number of veterans ending up homeless on American streets, begging or going insane. So it is only natural that Aiken, the younger son of Henry and Ruth, joins the army to be deployed to Kuwait and Iraq around Desert Storm. Luckily his deployment is short, though he has his share of war trauma but it has spared him more or less. Before he can quit the army, however, his second deployment takes him to South Korea, where he befriends an underage young woman interested in practicing her English with American soldiers and gets her pregnant towards the end of his tenure.

The novel opens with Aiken loading his truck with few of his belongings in order to move in with his parents while contemplating how best to stay in touch with his four year old son, Henry named after his father, a Navy veteran, and how to make sense of the distance which has opened up regarding his Korean wife.

Saturday, August 8, 2020

My Re-evaluation of noted writer Altaf Fatima's Urdu Novel Chalta Mussafir

A historian’s focus is on facts extracted from primary or secondary sources offering a counter-narrative. For example, in the US ‘the no taxation without representation’ narrative persists. Some historians have however argued that the fear of losing slaves caused the revolution. There were slave rebellions. Then King George III issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, forbidding white settlers from usurping more land from the natives.

Historian Gerald Horne argues that the revolution was, in fact, a counter-revolution spelling disaster for African Americans and Native Americans. When novelists enter the fray, they draw a narrative arc with ordinary humans at the centre. Altaf Fatima’s novel Chalta Mussafir was written about a decade after Pakistan army’s unconditional surrender in Dhaka.

Except for the weak ending, I loved her book Daskat Na Do (The One Who Did Not Knock, translated finely by Rukhsana Ahmed) for its diction and for situating two outsiders at the heart of the story. One would think that a decade was a long enough time to gain perspective about an emotionally charged moment in history, and weigh official and unofficial narrative and counter-narratives to offer an undidactic lens. An equal number of Hindus and Muslims don't have to die and en equal number of perpetrators of violence should not should not also be lined up. Since no one has a complete grip on the truth, the author must look far and wide.

Read the rest Here

Monday, March 2, 2020

My review of I'm From Nowhere by Lindsay Lerman