|

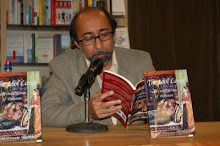

Murzban Shroff's recent collection Third Eye Rising is a deeply satisfying effort. In story after story one witnesses not only his compassion and controlled empathy for his characters but his desire to challenge the standard narrative. He keeps on pushing the boundaries of how far and wide he can stretch the limits of storytelling. The real pleasure of reading his stories, almost all of them, however, comes from discovering an additional symbolic layer wrapped around the narrative arc.

Take, for example, the leadoff story, "The Kitemaker’s Dilemma", which, on a cursory reading, appears as a straight forward story about a kind-hearted kitemaker, who develops a paternal bond with a scarred-skin, motherless boy locked inside his home all day while his uncaring father goes off to work. The kitemaker notices the shy boy behind the window curtain, becomes curious, hopes to connect with him and, failing that, learns the boy's story from another elder in the town: the boy's father not only killed his wife, he also shifted the blame on to the son, who ends up with a burnt skin. The kitemaker tries a new approach, leaving a kite for several days in a row outside the boy's window, which the boy does not touch. Yet by the time the kitemaker must move on, he has won the child's trust, and unbeknownst to his father, the child's kite has soared into the sky for everyone to see. A simple story about love's triumph! But a careful reading allows the reader to find several hints dropped by the author regarding what it means to be a writer/kitemaker: pondering over the kite or story’s size, design, strength and its development. Just as Murzban Shroff’s stories test their wings and soar into the sky, the viewer realizes the kite has acquired new contours. A story must be a chameleon, Shroff insists. A second layer appears. Just when the reader thinks it is the boy who must seize the center stage after much coaxing from the author, they realize that the story is not just about one kitemaker or one child left unloved, but the entire country of India caught in a tug of war between those who care and those who don’t. His stories become what Dostoyevsky calls "the human heart where good and evil battle each other".The second story, "Bhikoo Badshah's Poison", broadens the canvas. !e poison of a beggar king, if loosely translated. A situation, which grows embarrassing for the narrator as it exposes the flaws and innate inequality rooted in India's casteism, shifts the narrative, again, metaphorically speaking, from the kitemaker to the kite-flyer, from the benevolent bank officer/narrator to the clerk named Bhikoo Badsha/ protagonist. !e story, which begins with exploring the bank officer’s gullibility and Bhikoo’s harmless cunning, reveals an extra layer which connects Bhikoo’s actions - to get basic education, leave the conservative trappings of his village, send his son to an English medium school, visit his village on his motorbike and bring gifts - all result from Indian government’s abject failure to provide honorable life to the poor, such as basic health care and good education. !e poison inside Bhikoo is the societal one, which had killed little children after eating contaminated lunches due to the principal’s criminal negligence.

Murzban Shroff weaves micro and macro brilliantly like no other writer I have read in my recent memory. !e fourth and fifth stories, "Diwali Star" and "A Rather Strange Marriage" respectively, show his innate understanding and command over the socio-political fabric of modern day India that he feels is constantly being ripped and only a return to compassion and empathy can save it. "Diwali Star" revolves around an honorable retired police officer and his family. Despite having done everything within his power, he cannot control the disintegration of his family. Consolation comes from letting things go, not having his sons by his side on Diwali, and forging a bond with the night watchman, who has literally lost his only son. There’s a bit of a Nehruvian touch to the story, but the point the author makes is that human connection does not rely on blood or caste or religion. "A Rather Strange Marriage" pushes the narrative a bit further and in Shroff’s somewhat male-centric point of view, (and the author's sarcastic murmurs that belittle hollow patriarchy), women take charge of the action, if not the narrative. Even in this story, Shroff does not lose sight of the connection between the modern day feudal cruelty and debauchery, that comes at the cost of poor peasants (and 75 the free sex their women should provide), and the feudally-minded who insist on enjoying the entertainment cities provide. If the crops fail, the poor cannot pay the feudal masters; if the feudal masters cannot collect the taxes, they cannot pay for the fun in the cities. !e story bravely suggests one way to break the cycle.

The title story "Third Eye Rising", however, sets the stage for how "A Rather Strange Marriage" would end. Satinder Bijlee reaches a breaking point witnessing his father, a symbol of India’s deeply entrenched superstition and patriarchy, act cruelly and insultingly towards his daughter-in-law. Killing his own father without leaving evidence as the only solution to ending his and his wife’s misery may suggest that India is giving birth to a new kind of man, but it does little to shift the status quo from patriarchy to a more inclusive system. While most of the stories allow hope of a different kind, a fractured utopia of sort, perhaps, the title story says it bluntly that India has a long way to go.

Shroff’s major stories here use death as a driving vehicle, but they allow a rebirth as well. Except the longest one in the collection. "A Matter of Misfortune", which is most poignantly fleshed out. This is perhaps his ‘mini’ magnum opus. It is about two very close friends, opting different values and goals in life, with one meeting a tragic end because, the narrator, and by extension the author, suggests, is due to chasing an economic mirage, the lure of the American brand of capitalism injected into the veins of a shining India. But the story also offers a character study, and if I am not mistaken, a bit Balzacian. Look at the opening sentence, for example: "I was there the day Amit died. He fell from a height he was unable to handle."

It is told from the point of view of someone whose love for his friend is immeasurable, hence the name Amit. As the narrator mourns Amit’s death, he recalls the character development of his friend, the one who is driven to achieving his goals, someone who is not willing to settle for small blessings. !e narrator conjures up Amit’s obsession with soccer, especially during rain, the influence of a blockbuster Yadon ki Barat, which works as a catalyst to blur in Amit’s mind lines between reality and fantasy, and a sense of identification with actors larger than life such as Amitabh Bachchan, Dharmendra, and even Jack Nicholson. The story also tests the limits of deep friendships when other players are involved. All in all, it is a master stroke.

The last four stories are lighter and they serve well to allow a reader a breather. They also allow the reader a peek into the author’s skill at humor such as in "Oh Dad!". Murzban’s diction is rooted in realism and its flow keeps the reader glued to the characters' voices. He also very carefully avoids pontificating, thus raising the level of the stories much higher. Therefore, it is irritating to find easily avoidable distractions such as when the reader is unnecessarily reminded that the conversation is taking place in Hindi. Or when both a Hindi sentence and its translation occur in the same sentence as here: “Dhanda kaisa?” “How is business?” Baba Hanush asked, after the casual courtesies. Or: “They call him chotta bhoot, meaning little ghost.” When two people are talking in Hindi, why would a character feel the need to translate the expression in English? This kind of sloppiness should have been taken care of by the editors, if not the writer himself. While there is tremendous empathy in the stories, there is very little or no romantic love, which is the strongest device to break caste, religious, racial and economic barriers.

Finally, despite minor hiccups, what lends Shroff’s fiction staying power has to do with his observation that is grounded in moral/immoral reality. While the universe may be amoral, the world that we live in is not. It is laziness to think otherwise. Recognizing morality does not mean it is synonymous with sexual, religious, Victorian, patriarchal or national morality imposed on one by the powers that be. Rather it is something a sensitive artist develops as their own sense of right and wrong, along with several shades in between. If they don't have that, they've got nothing that’s of any real value. Sure, vacuity and denseness can be, and often is, presented as art, but it is the author/artist who cannot detect the morality in or of the work. Of course, I am talking about the author’s moral sense, not their characters, but a good writer learns not to conflate them. When the narrator of "Bhikoo Badshah’s Poison" informs the reader: “Morally speaking, I was bound to advise Bhikoo against the consequences of impersonation. But seeing his face I realized how important this might be for him . . ,” Murzban Shroff must be congratulated for having a moral vision that consistently negotiates his characters’ thews and frailties.