I called Peter back and explained to him that he might not be able to recognize himself in that scene but he is Yolanda, the white woman. Peter and his husband chuckled once again before saying goodbye. Wasn't that Ghalib who said آتے ہیں غیب سے مضامیں خیال میں ?

Wednesday, October 1, 2025

How (My) Fiction in my Novellas Works

The protagonist of the third novella - We Don't Love Here Anymore - feels suffocated in his relationship though he still loves his partner Yolanda, who is white, and her daughter from a previous relationship. As a result of the suffocation he feels, he allows himself to be distracted by other women. He has been flirting with an immigrant woman from one of the African countries, but as luck would have it, he also ends up having an unfulfilled, embarrassing sexual encounter with a close friend of his partner. In his despondent and lonely moments, he re-enacts the exact moment where he made the fateful decision to go home with the woman he is now living with after they left a party they'd just met at. A few days ago, as I staffed the Weavers Press table beside my friend Patrick Marks of Green Arcade and Ithuriel's Spear Press at the Litquake book festival, my ex-colleague Peter Warhit showed up with his husband whom he introduced to me. I told both that I could never forget that more than twenty years ago, just as I had switched from being a Page (a term we at SFPL use for shelvers) to a librarian after my MLIS and job interview, Peter had stood up for me. Peter's eyes widened as he seemed to say, Me? How? When? I was at the Info Desk and a rude patron had approached us and begun abusing me. Peter, scheduled at the desk with me and was mentoring me, not only scolded the patron by telling him to back off but that he could not talk to his colleague in that manner, refusing help. The lesson I learned was that I would have to stand up for my colleagues as well. Both Peter and his partner chuckled. As we exchanged surprises at having run into each other twice in a week and other pleasantries, he first congratulated me at having been at the library for 30+ years. Then he spotted my books and wanted to buy one of the novellas. He asked for my suggestion/preference. I explained that the three novellas were independent of the others and the only reason they fell under the canopy of San Francisco Quarterly was not because of the same characters propelling the story of their lives but because San Francisco itself was the main character, the San Francisco of my time, say, from 1985 to roughly early 2000, a time when the city's artsy, bohemian, intellectual, non-capitalist culture full of bookstores and cafes and art openings and readings and Small Press Traffic and ATA and Roxie and Red Vic and a dozen film festivals and weekend parties and people showing up unannounced to crash at friends' couches for weeks would come under threat by the techie world invasion, rising rents, corrupt Democrats and Starbucks' corporate onslaught on family owned rickety, grungy, casual, rich in character cafes. In the last 80s, the Mission District of San Francisco alone had 17 bookstores! So I told him that he should buy the third novella, which in reality was the first one I had written. I joked that he might recognize people in it, but then I clarified that the characters were composites. Instead of recognizing people, he might recognize a habit or event or behavior. As he walked away, I joked again, Hey, you might recognize yourself in it too. And then I remembered. The source of the protagonist's ballooning discomfort and sadness lie in the memory of how Yolanda had stood up for him at the party. The scene was based on a real-life incident. I was at a neighborhood party at the flat of a friend Mary Kinderman, who I have lost contact with though I keep searching for her because she was a wonderful, loving person. She had two roommates, Peter and David, both of whom were like friends. I'd often run into David in and around the neighborhood. He worked in photo journalism. Back then, we were all friends. Everyone knew everyone else, especially in the Mission District (and even beyond). During the party, the entire flat was abuzz, every room filled with people chatting, smoking, laughing, hugging, music blaring, couples kissing and so on. I along with a close friend crouched in David's room, on the floor along with several other people. All of a sudden, I don't know what got into David's head, he started ordering everyone to clear out of his room, clicking his fingers, like his mood had soured for a reason no one knew. Perhaps he was drunk. But whatever the reason, he picked me of the people, reaching for my collar and yanking me up and we all exited his room. I was angry with him, silently, for treating me like that, but I was also angry at my friend for not saying anything. But perhaps he, my anonymous friend, too was stunned and didn't know David because I had invited him to come along. My friend felt offended at the treatment meted out to me and yet because he couldn't stand up for me, left a little scar in me. So down the road, many years later, in the novella, I replicated that scene. Tufail shows up at a party and quickly befriends the only non-white person at the party, an African American woman. They both seem to hit it off, but then he is distracted by another woman, a white woman, who ends up attracting, stealing him unknowingly as the African American woman goes to the bathroom, and Yolanda steps in, fills the vacuum, and soon she and Tufail are enjoying getting to know each other as they distractedly move to another part of the house, sharing booze and toke, to end up in a room, where one of the hosts, a stand in for David, tells everyone to leave his room and go elsewhere, and ordering such, he grabs hold of Tufail's collar, but to his surprise, Yolanda scolds the host and tells him to stop it because Tufail is not his dog. This turn of event triggers the next move made by the two as they exit the party to end up at Yolanda's apartment and the rest is history.

Saturday, June 7, 2025

The Launch of a Dream - Weavers Literary Review

I knew I'd start a literary magazine dedicated to promoting and showcasing South Asian American writing one day. I just didn't know when it would happen. I have always admired the dedication and grit exhibited by my friend Syed Afzal Haider and team (English), Ajmal Kamal from Karachi (Urdu), and Maqsood Saqib and Faiza Rana in Lahore (Punjabi).

I learned the ropes over the years and I like to believe that I have earned the respect of my fellow writers to be trusted with their work under my custodianship to be treated fairly and with love. I have also been lucky to have been invited to put together two important collections: A Letter from India; contemporary Short Stories from Pakistan (Penguin, India) and Chicago Quarterly Review's The South Asian American Issue.

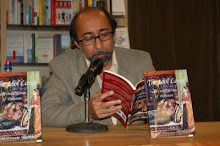

My wife and artist, Amna Ali, has been a constant presence in this endeavor, from designing to proofreading to creating the order in which poetry and prose jostled for space. With mutual agreement, we decided that we didn't want Weavers Literary Review to be a platform of exclusivity but rather of inclusivity. That's why we wrote on the inside page A Home for Writings by South Asian Americans and Others. The Others are more than welcome! That is our message. We are writers and our roles is to teach empathy and build bridges and challenge status quo and hatred which politicians and foolish think tanks and lobbyists throw in our path. It was my honor to be able to set the inaugural reading at my favorite bookstore Adobe Books in San Francisco on June 5. The readers who graced the occasion were in the following order: Naia Chien, Sophia Naz, Mira Pasikov, Shikha Malaviya and a surprise appearance by Brian Ang, whose work will appear in the next issue. Unfortunately Ujjagar and Monica Mody couldn't make it to the reading. We missed you. It turned out to be a jam-packed session, from fellow writers to close friends to new friends I had met recently at cafes and book fairs. After a brief session of Q&A, wine flowed and strawberries crunched, a conversation among friends and acquaintances, old and new, enriched the music Ryan, an excellent host, had put on.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)