I called Peter back and explained to him that he might not be able to recognize himself in that scene but he is Yolanda, the white woman. Peter and his husband chuckled once again before saying goodbye. Wasn't that Ghalib who said آتے ہیں غیب سے مضامیں خیال میں ?

Wednesday, October 1, 2025

How (My) Fiction in my Novellas Works

Saturday, June 7, 2025

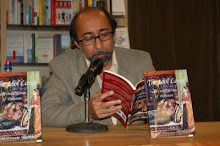

The Launch of a Dream - Weavers Literary Review

Wednesday, December 11, 2024

A Poem by Ujjagar

Nation’s Lost

Learned men talk of the news

What’s happening away from their views

The things they don’t need to see

Because they’ve got their degrees

The rockets launched by a group

The marching of military boots

But not the bodies lying in the mosque

Hush Hush

Their voices cry

If we speak too loud They’ll pass us by

So we quietly whisper

I don’t think it was justified

There are too many children trapped inside

How long has this been going on

Why do they talk only to decry the violence of one side

Hush Hush

You’re being too loud the learned men say

The cameras will go away

Our shackles are rattling, roaring now we wonder how long will they drown them out

The stones children throw have prayers written within

But no learned men seem to have read the prayers or seen sin

HUSH HUSH

No

These learned men talk

And they talk so loud that we fear the world won’t be able to hear the planes and bombs

Won’t hear the cries of a mother losing their child

Won’t hear the howling kids who’ve lost limbs

Won’t hear the silence

The silence that screams loudest of all

The silence of a people killed off

A nation lost

Tuesday, November 7, 2023

Regarding Our Complicity! Part I

Continuing with a similar tactic, recently, Fox network's intellectually infirm Sean Hannity had on his show Cornel West and Alan Dershowitz discussing the tragic loss of men, women and children at the beginning of the new cycle of violence between Israelis and Palestinians, the occupier and the occupied, while the host playing clearly on the side of the occupier and missing the point that victims are seldom passive, who can and will strike back and commit acts of violence, too, a la Nat Turner, to cite one example from the page of African American history. Many readers of the world history would, or should, know the watershed event often described by two names: 1857 War of Independence and Rebellion of 1857, depending on the points of view of the colonialists and the colonized. The uprising against the British was brutally crushed, but before that the natives, too, committed acts of brutality towards the British, including women and children. The great of poet of the time and resident of Delhi, Ghalib mourns and condemns as such in his letters. To assume that the colonized/occupied/brutalized will not retaliate or strike back or commit murder of civilian population stems from our racist tendencies to view the defeated as incapable of fighting or writing back.

Now back to the pairing of Mr. West and Mr. Dershowitz. Both are religious, to begin with, but fair enough since they represent two opposing poles of American political landscape. Now, both academics, but Mr. Dershowitz has been accused of plagiarism by Norman Finkelstein in a very well-known encounter on Democracy Now. You can watch the entire exchange here. Scholar Norman Finkelstein Calls Professor Alan Dershowitz’s New Book On Israel a “Hoax”.

Let's backtrack a bit. Norman Finkelstein had discovered after a thorough reading of Joan Peter's book

From Time Immemorial was a complete hoax. In a very informative article, Prof. Chomsky writes about it here:

What do you think?

Peace and justice!

Monday, August 21, 2023

Spanish Memories

In August 2023, my wife, our two sons and I braved a two-week trip to Spain - Madrid to Seville to Granada to Barcelona to Madrid again - under the average temperature of 100-degree heatwave, which we survived. The excitement of being in Spain so rich in history worked as the invisible umbrella over our heads. For me personally, it's hard to pick a favorite, but if I were given a chance to go and live there, I'd choose Madrid and it's hard to explain why I say that. Whenever I travel, I'm always more drawn to speaking with people I meet whether they are travelers like me or native. A few interactions stood out. On our second day in Madrid, we ended up in a Pakistani restaurant near Gran Via. The food was good, but the most surprising part was to find the cook speaking to us in fluent Punjabi, but when I enquired what part of the Punjab he hailed from, his reply left me speechless: Nepal, I'm from Nepal. He blamed it on the people he'd been working with for several years. Another hilarious moment presented itself when we went to a Pakistani restaurant in Barcelona where the waiter/owner tried to dissuade us from drinking tap water instead of the bottled one they sold. He said he would, and did bring us, tap water but added that he wouldn't drink it himself because Barcelona water was bad and would give your tummy a run for its money, adding that the reason being that the tap water came from the beach where all kinds of people swam. I freely drank tap water in Spain though being addicted to San Francisco water (courtesy of Hetch Hetchy reservoir) doesn't help and I was fine. One fine interaction occurred when my younger son and I went into a cafe where I engaged a young barista in a light conversation. I forget her name as I write this but she was a native of Madrid and though she had traveled to the South, she had never been to places such as Seville, Cordoba or Granada, so she was obviously very envious. She shared with us that most young Spaniards live with parents for extended period of time because the wages in several sectors are low. Once she heard we were visiting from San Francisco, she couldn't control her excitement and probably that's why she made an excellent single espresso, something which, sadly, most cafes in San Francisco can't crank out anymore. (Just today I ordered a single espresso at Earth's Cafe on Geary St. and got a loaded triple, but café owner insisted it was a single. Sigh! I drank one-third and left.)

In August 2023, my wife, our two sons and I braved a two-week trip to Spain - Madrid to Seville to Granada to Barcelona to Madrid again - under the average temperature of 100-degree heatwave, which we survived. The excitement of being in Spain so rich in history worked as the invisible umbrella over our heads. For me personally, it's hard to pick a favorite, but if I were given a chance to go and live there, I'd choose Madrid and it's hard to explain why I say that. Whenever I travel, I'm always more drawn to speaking with people I meet whether they are travelers like me or native. A few interactions stood out. On our second day in Madrid, we ended up in a Pakistani restaurant near Gran Via. The food was good, but the most surprising part was to find the cook speaking to us in fluent Punjabi, but when I enquired what part of the Punjab he hailed from, his reply left me speechless: Nepal, I'm from Nepal. He blamed it on the people he'd been working with for several years. Another hilarious moment presented itself when we went to a Pakistani restaurant in Barcelona where the waiter/owner tried to dissuade us from drinking tap water instead of the bottled one they sold. He said he would, and did bring us, tap water but added that he wouldn't drink it himself because Barcelona water was bad and would give your tummy a run for its money, adding that the reason being that the tap water came from the beach where all kinds of people swam. I freely drank tap water in Spain though being addicted to San Francisco water (courtesy of Hetch Hetchy reservoir) doesn't help and I was fine. One fine interaction occurred when my younger son and I went into a cafe where I engaged a young barista in a light conversation. I forget her name as I write this but she was a native of Madrid and though she had traveled to the South, she had never been to places such as Seville, Cordoba or Granada, so she was obviously very envious. She shared with us that most young Spaniards live with parents for extended period of time because the wages in several sectors are low. Once she heard we were visiting from San Francisco, she couldn't control her excitement and probably that's why she made an excellent single espresso, something which, sadly, most cafes in San Francisco can't crank out anymore. (Just today I ordered a single espresso at Earth's Cafe on Geary St. and got a loaded triple, but café owner insisted it was a single. Sigh! I drank one-third and left.) In Barcelona, we met a group of very charming young Italian women (either late teens or early 20s), at the tail end of our visit to Sagrada Familia. Due to heat and a lot of walking, everybody was tired. The young women were sitting next to me and trying to take a selfie when I injected my presence into their life and offered to take their picture. In turn they took ours. And I began talking to one of them, the leader type. They were from Rome and all into foreign languages, and since then we have exchange a few emails. I asked the leader - Serena is her name - to share with me their favorite Italian writers and here's what she wrote back:

In Barcelona, we met a group of very charming young Italian women (either late teens or early 20s), at the tail end of our visit to Sagrada Familia. Due to heat and a lot of walking, everybody was tired. The young women were sitting next to me and trying to take a selfie when I injected my presence into their life and offered to take their picture. In turn they took ours. And I began talking to one of them, the leader type. They were from Rome and all into foreign languages, and since then we have exchange a few emails. I asked the leader - Serena is her name - to share with me their favorite Italian writers and here's what she wrote back: After talking with the girls, we've agreed on some Italian authors who stole our hearts and whose works you might appreciate.We especially recommend Umberto Eco (his mystery book "The Name of the Rose" was a quite complex read but definitely worthy of mention), Italo Calvino (you might know who recommended this one), Luigi Pirandello (I personally find his philosophical reflections on the concept of identity quite brilliant, especially in "One, No One and One Hundred Thousand").Cesare Pavese, Michela Murgia and Marco Balzano are very interesting as well.We tried to be a bit general but if you're looking for something more specific, you might ask with no worries!Here's the picture you kindly took of us at the Sagrada Familia, we'd be happy to be in your blog!(As for our names, from left to right: Elisa, Chiara, Elisa, Sonia, Serena and Federica).

Wednesday, May 24, 2023

Let Me Touch Your Mind: an interview

Thursday, May 4, 2023

Words of warning after reading A Footbridge to Hell Called Love

What a pleasure to see your email after returning from a short trip. I finished your book just before we left. There's something wonderfully approachable about short novellas. A Footbridge to Hell Called Love really brought back a lot of memories for me, having lived in SF from 1982 to 2004, a fair amount of that time in or near the Mission. I appreciated your focus on the emotional side of the creative life in the book. There were quite a few moments that moved me deeply. I really enjoyed the book and am curious about the other volumes in the Quartet. Are they all currently available?

I just want to let you know that I just finished your book, "A Footbridge to Hell Called Love." I found myself very absorbed in it and finished in 2 sittings. (picked up the 2nd time on page 47) It truly captured the essence of San Francisco and was very insightful. I was genuinely impressed how you developed the characters, captured their thoughts, moods & nuances.

As someone who has lived in the Bay Area for a while, you really nailed some parts well. I really enjoyed it and glad I read it. It really showed me a lot of work and thought went into it.

Bravo!

Sincerely,

Peter

Speaking of new work, I enjoyed A Footbridge to Hell Called Love which I finished a few weeks ago. Congrats on that! The first movement, the extended party scene at the Victorian house, where Aslam is bouncing about, buffeted by sensations, desires (“hot-hot” Andrea), envy, , the musicians and readers, Shirin, seeking Debbie - all of it seemed a perfect encapsulation of that post-college age, that mixture of promise and pretension, hope and disappointment, awash in cultural theory, when a backyard party seems the turning point of an entire life story. This quotation came to mind when I was reading it . . .

“I was passing through one of those periods of our youth, unprovided with any one definite love, vacant, in which at all times and in all places—as a lover the woman by whose charms he is smitten—we desire, we seek, we see Beauty. Let but a single real feature—the little that one distinguishes of a woman seen from afar or from behind—enable us to project the form of beauty before our eyes, we imagine that we have seen her before, our heart beats, we hasten in pursuit, and will always remain half-persuaded that it was she, provided that the woman has vanished: it is only if we manage to overtake her that we realise our mistake.”Marcel Proust, Withing A Budding Grove (1918)

The second movement with Shirin at the park is really evocative and well written, wonderfully done. The last movement is very touching and really makes you think of the strangeness of time, the what-ifs and could-have-beens.

Great stuff!

Take care,

Patrick

Moazzam Sheikh's novella, A Footbridge to Hell Called Love, is a rich read. The first part of the book describes a glorious time in San Francisco in the 1990s, when someone looking for cultural edification and lively conversation could wander the inner city and easily find like-minded souls looking for same – along with a side of sexual adventure.

That first section of the book was a moment-by-moment recounting of a boisterous house party. The writing was similar to watching a hand-held camera following characters in and around a scene. The dialog part was colorful – to say the least! For me, it credibly reflected the quick banter of a very particular social set.

For someone like me who didn't live in San Francisco during that era, I relished a glimpse of what I might have missed. Some pages in, though, I was relieved to be released from that opening party and move on.

The second and third parts of the novella made more of an emotional impact on this reader. Once the action slowed down a bit, I could ease into the psychology of the protagonist, Aslam, and the other characters who made the cut. The changes in their lives that took place rather surprised me, which is a good thing.

Thanks for letting us know about the novella, Moazzam, and good luck completing the rest of the series!

I just finished your novella A Footbridge…

I loved it. I was delayed a bit before I could start it (another library book with an earlier due date), but once I got into it, I basically couldn’t put it down.

The entire book from the energy and confusion of the initial 20-30 somethings party scene, and onto his temporary almost accidental relationship with Amelie, then to the Stephen Daedalus trek through SF with Shirin Ghobadi (a Persian Holly Golightly?) through making peace without ever forgetting Debbie and finally arriving at Aslam’s deeper, mature connection with Barbara that literally bears fruit both in their writing and their progeny. A portrait of the artist, indeed.

Your compelling story that resonates with me as I see myself in many of the scenes and situations. You subtitled it “San Francisco Quartet, Novella I”. I excited to see what comes next.

I got it and have read it. A shift in South Asian American writing? To

multicultural American writing? It’s about a young man’s shift from a

preoccupation with sex to a preoccupation with love, and in San Francisco’s

youngish literary set, which I can only assume is realistically portrayed.

Not sure what is South Asian about it, and maybe that’s the shift, to a

broader entangled identity.

First of all there is some lovely language here.

"their mouths turning into tropical caves"!

"voice splintered into tufts of dust"!

I wasn't initially sure what to make of the insight we are given into guy-mind, but then Aslam's character deepened into a sensitivity, self-awareness, and awareness of others beyond melancholic filters. Good for him! I am curious how he will continue to grow, and curious about the narrative development as we move through the series.

What an amazing sketch of SF in three movements. I have to say the party in the first movement reminded me a lot of parties in Delhi in the early 2000s. How interesting that young artists everywhere have the same patterns when they come together.

So glad Barb and Aslam refused to turn middle class. Finally, a beautiful ending. That last line!

I send a big round of applause to you both, for the writing, the proofing, the editing, and the fantastic cover art. Well done, and I look forward to the next one!

-Doreen

Thank you for taking the time to read the book so thoughtfully. It was a risky endeavor to write such a book where almost every character is a composite of so many people I have known for the last 35+ years of my life in SF. One wrong move and I could've upset someone. I had to tread where angels wouldn't dare, so to speak. This book would not have been what it is now without Amna's help, with language and tone and other errors of judgement I'm prone to make.

With your permission, may I share your comments with others on my blog?

p.s. we're working on the second volume currently.

-Moazzam

Yes, you can share my comments. Even though I don't know your friends (or maybe I do, SF is a small town), I also had moments of recognition! You really captured the characters in this town. Bravo!

love

vivek

Dear Moazzam mus,

Greetings from Bombay! It's hot and muggy here but I'm eating delicious food and having the best time.

I wanted to write as I finally had the chance to read your novella this last weekend. I devoured it in one sitting on the flight from Kolkata to Mumbai and felt a stab of panic when I reached the end — I was totally hooked and unprepared to leave the story so suddenly. But then I remembered this is only the first of a quartet (is that correct?) and felt relieved. When will we get to read the next one?

I just think the character of Aslam was so finely drawn — he was infuriating and exasperating but I found myself strangely attached to him. I felt all his loneliness and his joy (and when he starts secretly meeting Debbie behind Barbara's back, I wanted to jump inside the pages and yell at him). You created a whole world inside his head — and amidst all the insecurities and anxieties and uncomfortable fixations that existed there (around women, sex, intellectual posturing, class difference, etc etc), there was this wonderful core of perceptiveness and vulnerability and humor. It kind of snuck up on me how genuinely funny Aslam is — and how he's kind of laughing at the world even as it bewilders and overwhelms him. I laughed out loud more than once on the plane. There were so many lines I loved — noted down a few favorites, which I'm just copying below.

Anyway, I just wanted to tell you how much I loved the book and am really looking forward to reading more.

With love,

- Mehru

--

"Eddie's eyes narrowed as if they were protecting a pleasurable memory."

"he suspected it could have been a man she followed only to either lose him to the fog or let go once she found her own footing on a rare bright day."

"If they had a conversation, its memory, he was sure, would flap its wings through the forest of their private thoughts for a long time as they'd just touched the wings of a dream."

"..it was not healthy to carry another person's grave in the heart. The heart was not a tomb."

"Suffocating thoughts swirled around in his head...revealing to him how the monster of unpredictability hovered so close to ones world..."

"But what if the ending didn't give a fuck?"

Just finished your novel and much enjoyed it. Path dependency, private inner life and the unpredictability agency of others. Some nice turns of phrase and observations. Reminded me of Kierkegaard’s “life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.”

It was great to be able to read your fine complex novel. Please let Amna know how much I like her cover.

There is a time in most of our lives when we live almost exclusively for our lovers and friends. This is depicted beautifully as Aslam progresses along the path of love with Amelie, Barbara, Debbie. Along with a memorable interlude with Shirin. Other characters in his shifting friend group also held my interest. I wonder if l will ever find out whatever really happened to the bath-fearing David?

But ultimately it was Aslam who held my attention. Socially principled yet sometimes a literary snob, self-aware yet impulsive, calculating yet ultimately simple in his desire to love and be loved. And funny! He made me laugh a lot.

I look forward to the second novella!

Very, very good writing, old friend!